Red Rock Rabbit Ranch

/Martin Krafft

1.a. Too-tight shirts

After Grammy Bobby died, my nuclear family descended upon the farmhouse to process her former possessions. Grampy certainly would never have gotten around to it. Cleaning was not in his nature. My mother, my brother, and I attempted to sort through Gram’s overflowing wardrobe. But we, like Gram when she’d been alive, struggled to let go. In an effort to keep close her memory, we took some of her clothing for ourselves.

“That shirt’s too tight,” my mother told me.

“No, it’s not,” I said.

“Your stomach is showing.”

“That’s ok.” Then, “Well, at least this shirt isn’t too small for me.”

“Yes, it is. And it has a stain.”

“Almost all my shirts have stains.”

“Sounds like you need new shirts.”

Wearing the clothes provided a physical manifestation of her ongoing impact on us. We wanted to maintain her presence, to prevent her from fading into obscurity. Grampy might have thought it rather macabre, the three of us putting on his dead wife’s clothing. If so, he kept it to himself. The macabre did not deter us. There was a pride that I got from wearing her shirts, a sense of tradition maintained. The act was part of my at times obsessive desire to mourn her that also included my moving into the farmhouse with Grampy David six months after her death. Twenty-six-years old and unsure what to do next, I retreated to the countryside, to what I intuitively considered my homeland, though I had spent relatively little time at the farmhouse. For nine months, I lived with Dave, trying to understand Gram’s life and death, trying, too, to enforce some degree of order on the place. Both efforts were not successful in the way that I’d hoped.

1.b. Too Much Space

Reading through old letters hoarded by my grandmother, I found one from a friend of hers who had moved south. “I’m happy to be out of the cold. I don’t miss the old place at all.” I was struck by the words, as it was a sentiment that Grammy Bobby would almost certainly not have felt had she been forced to move. As it was, she lived the last fifty years of her life at the 200-year-old farmhouse at 127 Game Farm Road, Schwenksville, PA, accumulating stuff. What made matters worse for the accessibility of the house was that Grampy David, too, was a hoarder. He got half of the basement, the barn and all the sheds. She got everywhere else. Boxes filled first the basement, then the unfinished part of the attic, then the finished part of the attic, then Ann’s old room. Gram did not want to move because that would have meant having to sort through her stuff and deciding what to get rid of, a task which she was by herself patently incapable of. After she got pneumonia, though, some degree of sorting became a necessity. My mother staged an intervention in order to clear walkways through the house. Once she got into the swing of sorting, Mom would not be deterred from charging onwards in an effort to impose order. Gram was not necessarily appreciative.

“Keep what you really like,” my mom told her, eying the stuffed closet.

“I like it all,” Gram pouted. “That’s why I got it.”

“But we’re trying to simplify.”

“I don’t want to simplify.”

“But it’s so messy.”

“It’s a good thing that you don’t have to live here.”

2. Too Many Secrets

After graduating from high school, David Blackwell lacked an idea of what to do with his life. His sister had little patience for this lack of ambition and pressured him to join the Air Force. After surviving the military, he went to work as a technician on one of the first computers. He was still begrudgingly doing computer work several years later when he moved to Pennsylvania and rented a room from my grandmother. She was 49 at the time but told him that she was 39. He was 27. He did not discover their actual age difference age until her first pneumonia hospitalization, 46 years later.

Gram had been running a landlady operation on and off since being orphaned at 19. Bobby and David went into business together, with Grampy also thrust into parenting Ann, age 12, and my mother, Cairn, age 6. He did not ask questions about Gram’s past, and she did not ask questions about his. They both wanted to start afresh, to mold a new world for themselves, not necessarily together, but that was the only financially viable option. Together, they could afford the house, get out of the city. Gram found it harder to escape whiskey. She spent most of my mother’s childhood downing scotch. Grampy had no idea what he was getting himself into, marrying an alcoholic with a pubescent daughter who had little patience for a new parental figure.

3. Too Many Rabbits

The proposal was by no means a romantic one.

“My wife and I will take it,” David Blackwell said to the realtor.

“Oh?” Gram said to David later. “I guess we’re getting married?”

As my grandmother explained decades later to a family friend, “I had two girls who wanted horses. It was a farmhouse. What was I supposed to do?”

The wedding was not a large to-do. All my mother remembers of it was that she wanted to get home to watch Mr. Ed the Talking Horse. There wasn’t much need for ceremony. This was Gram’s third marriage.

Fifty-three years after my family moved into it, the farmhouse house retains a quirky charm. It must have been a beauty to behold when they moved in, both massive and maintained. Now it is just massive. For my mother, it was a dream home. A towering school bell to ring at the entrance, a pond to watch the ducks a-dabbling, a creek to scour for crawfish amidst the reddish-brown stones. Woods to walk in (given her mild nature, I imagine she was not much of a childhood runner), a pool to swim in.

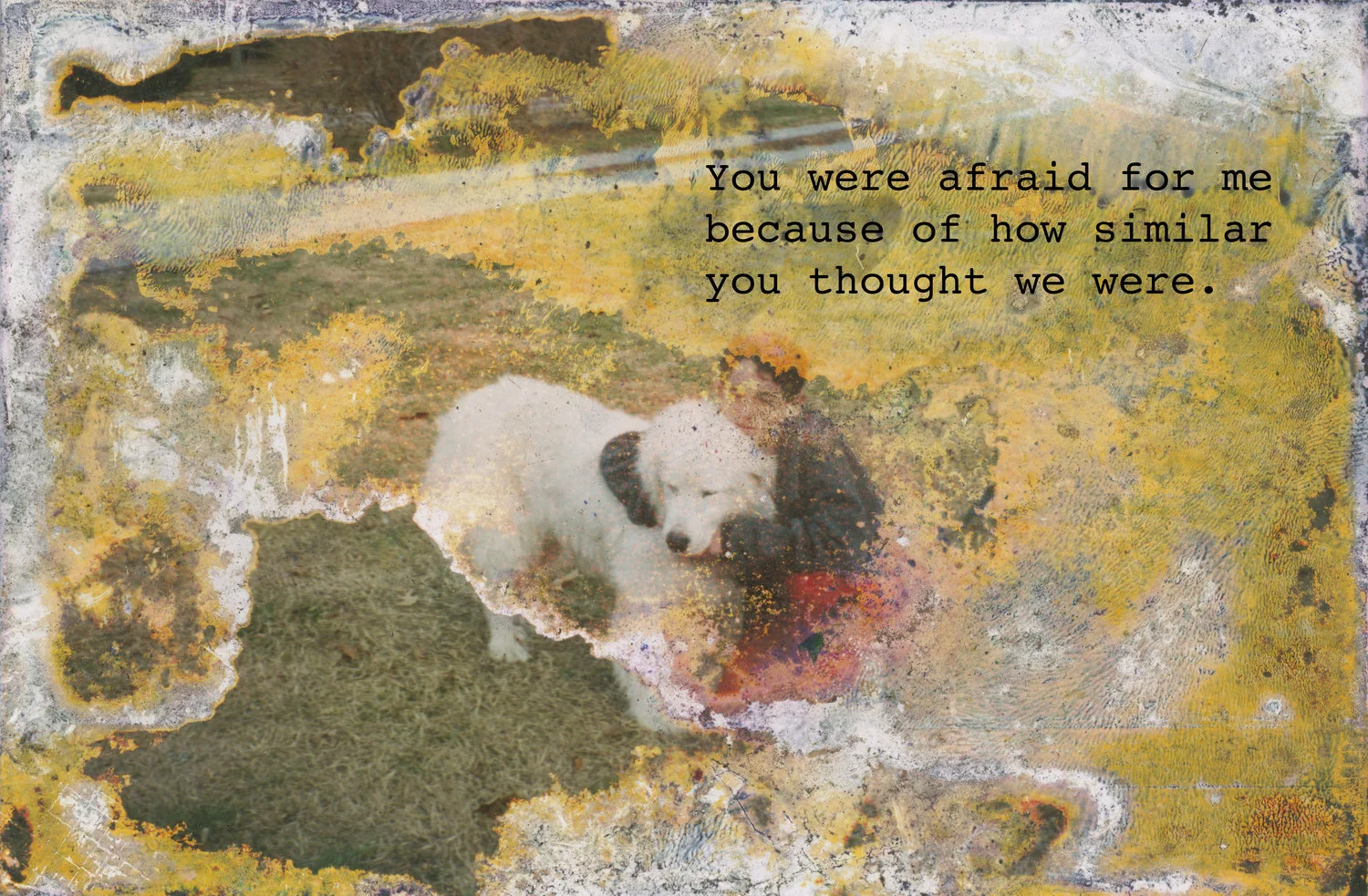

Prior to the farmhouse, single-parent Gram had refused all requests for pets. Once they got to the farm, though, the pets started accumulating. There was not just a horse, but its donkey companion. The owner of said donkey had wooed my grandmother by describing it as a “Sicilian donkey, with a cross on the withers. The kind like Jesus rode.” My grandmother was not much of a religious person, but surely this appealed to her sense of a bargain. The donkey turned out to be appropriately ass-like, though, to the point of trying to bite my aunt whenever she fed him. There was the beagle, LD, dumped at the farmhouse, and then Fluffy. Grampy postured as not wanting another dog, but he secretly fed Fluffy in the barn. He was indeed surprised when he discovered that Gram, too, had taken to feeding the dog in the barn. At last the dog was allowed in the house.

And there were rabbits. Two boys, my family thought. Then there were baby rabbits. They put Maxwell now Maxine in a different hut, but she had already been impregnated a second time. As the rabbit population ballooned from 2 to 22, Grampy devised a name for their new home as Red Rock Rabbit Ranch, one of the more poetic outputs of his life.

4.a. Too Much Hallmark

One would not be inclined to think of Grampy as a romantic, but he was certainly dependable. He did not complain and did not ask questions. He worked hard at maintaining the properties they acquired as part of their house renovation operation in the area. In sorting through Gram’s letters, I found birthday and Valentine cards that he had written her every year. They were all of a similar style, big cards with glaring letters declaring their love. “Dear Bobby,” and “Love, David,” was all he wrote, leaving Hallmark to fill in the rest. A single birthday card stood out, though: he had also written, “I’m glad you are my wife.”

She, in return, scolded him often.

“Are you ever going to fix that window?” And, “When are you going to repaint this room?” And, “When are you going to redo the floor?”

But as she lay dying in the hospital, almost comatose, she called out “Dave,” looking for his reassurance.

4.a.i. Too Much Plastic Santa Face

Once I moved in, my efforts to “help” Grampy sort through his stuff met staunch resistance.

“Why do you have four weed whackers?” I asked as he rooted around the tool shed looking for a screwdriver.

“I don’t know which one’s work.”

“You could find out.”

“I could.”

“And get rid of the ones that don’t work.”

“I might be able to fix the ones that don’t work.”

“Are you ever going to clean up?”

“Tomorrow.”

He kept the four weed whackers. When I finally convinced him to sell one of the four dehumidifiers, the other three died and he was forced to buy a new one. After that, there was no more sorting. Gram’s stuff, though, he was ready to see go. The one item which he seemed to have any sentimental attachment to was a hideous, plastic Santa Claus face.

“That’s the last thing she bought,” he said.

Gram had two very different tastes, the refined and the maudlin. Plastic Santa face was certainly the latter. I stashed the face out of sight, unwilling to see it go but not wanting to look at it either. My desire to understand Gram, to keep her close, warped into a compulsion to clean, to make manageable the house that had for so long been overwhelmed. Living in the house meant clearing out Gram’s stuff, her trace in the house. The stuff reflected her. Its accumulation reflected her. The choice of what she chose to bring home reflected her. Her inability to organize reflected her. It mapped her simultaneous sophistication and sentimentality. It mapped her singularity.

4.a.ii. sophisticated: having, revealing, or proceeding from a great deal of worldly experience and knowledge of fashion and culture

She could recite Longfellow from memory, pick out name brands at the thrift shop (a task which I had little interest in), and had undoubtedly accumulated a “great deal of worldly experience” in her youth. But there was another part of her that cared little for posturing, that was moved by emotions and had no problem being moved by emotions. It was the part of her that donated to every animal charity that requested money from her, though she was perpetually unwilling to spend on herself. I came to disdain the cute things she had collected, as if by removing them I could change who she had been, make her more sophisticated in memoriam. Why did I want to change her? Because I wanted to be changed. Recovering from a failed romance, I sought to drive that sentimentality out of myself. Because sentimentality was perceived as weakness, naiveté. Because I wanted to be strong, invulnerable to Gram’s death.

4b. Too Many Cabinets

If Grampy David ever ends up moving, it will be begrudgingly so, because he is no longer fit enough to maintain the property. He is not necessarily planning on having to move.

“What’s your five-year plan, kid?” he asked during my recent visit to the farm.

“Hell if I know. What’s yours?”

“My five-year plan is to die,” he scoffed.

If forced to move, he will begrudge having to give up all his tools and assorted knickknacks accumulated over the past 52 years. There is a barn, pasture house, and five sheds full of these possessions, some of them still useful, many of them less so. Once beautiful wooden pieces of furniture, mostly intact upon acquisition, now ruined by rodents and moisture. Tools for any number of tasks, oftentimes multiple versions of them. When he was in the process of retiring from home renovation work, he could not restrain himself from buying not just one but three sets of kitchen cabinets that still live somewhere in the barn. At least a dozen fans, some of which might even still work. Old doors. A bow and arrows. At least a dozen once ornate chairs. There are also the barns-within-the-barn, wood from two dismantled barns picked up from the side of the road. These are by no means all worthless items; hipster bars would love to get their hands on old barn wood. But the sheer amount of stuff makes the task of organizing seem insurmountable. The barn alone is so full of stuff that Grampy once found a dead deer inside; the deer had stumbled in and been unable to find its way out.

Grampy gets older. What at once seemed like a vague possibility, the cleaning of the barn, now seems wholly untenable. Though incredibly fit for an 81-year-old, he is still an 81-year-old. One day, he will be too old to continue maintaining the property.

4c.i. Too Much Reproduction?

Walter Benjamin wrote about the loss of aura, of authenticity, that results from being in an age of mechanical reproduction. Because we can reproduce art photographically, art loses its air of uniqueness. Whenever we see the original, we have probably already seen some other version of it. We think we know what to expect. We cannot be awestruck by the expected. In his analysis, Benjamin does not seem to offer a definitely positive or negative assessment of this death of aura. As a Marxist, he is at least somewhat satisfied by the flattening of hierarchy that accompanies the flattening of aura.

I am not convinced that aura has been wholly lost, though. The Red Rock Rabbit Ranch radiates aura: the three cast-iron wood stoves shoved into the giant fire place, gas lamps that haven’t been used in decades, tiles along the mantel that Gram hauled onto the plane back from Mexico, flooring made from former barn wood. An array of dented pewter ware nabbed at flea markets (the undamaged variety was too expensive). A tray of pottery pieces found around the property, the long, thin couch that Grampy slept on every night for the last 20 years of their marriage. Clay pots full of Gram’s old Women’s Club Annual Reports. By reducing the stuff in the house, I was also reducing the aura of the house. The aura is Gram. The aura is Grampy. It is their selves transmitted into and through the building.

4c.ii. Too Much Heat

Red Rock Rabbit Ranch is also place as receptacle of trauma. The drinking, and the rabbits. Ann and Cairn were at home one day, with one of the tenants. They heard strange noises from the rabbit pen. “We need to do something,” Ann told the tenant.

“No! They could be sick. They could be contagious. Stay away.”

By the time Dave and Bobby got home, three quarters of the rabbits were dead. They’d had heart attacks from the heat.

4.c.iii. Too Much Whiteness

When I go back to visit, a year after leaving, I share Grampy’s dread of the eventual loss of the

farm. When he is too old to maintain the property, he will have to sell. He doesn’t have enough money otherwise. He was not a very good investor, already owes tens of thousands of dollars of back-taxes on the property.

Why are we afraid to lose the farm? He is afraid because he has some degree of dominion over the space, a place where he decides what and when he wants to do each day. I am afraid of what the space will become. It is not hard to imagine. Driving around town, there are plenty of farms that have already been converted into row after row of endless subdivisions. The old trees are cut down, only a few planted in their place. The lawns are indistinguishable. The houses are indistinguishable, except to the people who live in them. And surely, they are glad to have a space to call home. But it is not a home with a sense of place. Not as Ed Casey considers place, place as particularity. The suburb is a death of place. The suburb is interchangeable. It can be anywhere. It forces the land to adhere to it. It is a negation of geography, a negation of singularity.

It’s apparent that suburbs are placeless because Judith Chafee’s desert architecture offers a vision of architecture as place. In a landscape that people often struggle to master, a land of dirt yards and mesquite thorns, her buildings meld into the land around them. The buildings are not in spite of but because of the desert. They are expensive, though. The plans are expensive. The materials tend to be expensive. It is expensive to take the time to understand the land. There are no easy answers for responsive yet affordable architecture.

That the farmhouse, so full of history, my own family’s and others’, might soon be subdivided, is a thought that spurs me to anger. It is a feeling maybe not too different than what aristocratic families felt upon having to give up their estates, not a sentiment one would expect from an unapologetic socialist. I do not need to own the land, but I want to be able to access it. And even if I cannot access it, I want to know that it exists, in some continuous form, maintaining even a sliver of its presence, of its aura. As part of a white culture often cut off from a sense of heritage, the farm grounds my family. Its destruction will feel like an attack on not just the land but my family.

As suburbs are a destruction of place, whiteness in its current iteration is a destruction of tradition. It is a flattening of Irish, German, French, Swiss, Russian, Ukranian, Scottish, Welsh, Belgian, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Hungarian, Romanian, Greek, Macedonian, Polish, etc. culture into a mass consumer culture, an entity that is designed to be like a cat chasing a laser pointer, endlessly distracted, endlessly unfulfilled.

But who am I to lay claim to the land? Who, even, is my family, inhabiting the place for the past 50 years? Fifty years is only a quarter of the building’s life. Before that, the house belonged to a judge named Striker, who called it the Bald Eagle Ranch, even painted the name on a rock outside. Gram wanted to rename it Goshawk Farm, after the original house inhabitants, but Grampy was the one who got to the paint first. Striker did not live in the ranch but treated it as a summer home, a getaway from the city where he ran a high-stakes poker game. Before that, there was Royce, another city slicker seeking city getaway. And before that, for a hundred years, the Goshawks, a family of Mennonite farmers, who built the home. How many fucks, how many meals eaten, how many sicknesses, shits taken? How many had walked this same creek, seen the same sycamore trees? The only reason the sycamores had survived, compared to every other old tree, was that the wood was not good for burning or building. They were the only trees that lived to look out over the farm, to watch as the humans who inhabited it died and were replaced.

How do you feel a sense of ownership over land that has so much of others’ history? Before whiteness descended upon North America, the Lenni-Lenape lived there in matrilocal societies in which children stayed their whole lives with their mothers’ family. Couples came together to bear offspring, then returned to their respective homes. Their structure created an emphasis on female leadership not so different from Gram’s matriarchal role in the family, centuries later. The land on which the house was built was ceded to William Penn to create the state of Pennsylvania. While Penn strove to be kinder to his indigenous neighbors than all other states, that friendliness still went hand and hand with displacement. The Leni-Lenape, forced to move all the way to Oklahoma in order to survive, could also lay claim to the land. Does their claim invalidate my own sense of connection to the place? Are these claims mutually exclusive, or additive? What would a land ownership model look like in which all of our claims were granted some degree of validity? I don’t think Grampy would be too appreciative if I told him some Leni-Lenape were moving in.

It is not as simple as “white man conquering Indian,” either. The Leni-Lenape caused displacement of the mound builder cultures that inhabited the land previously. History is an ongoing accumulation of displacements.

5. Too Much Trauma

The most obvious explanation for Gram’s hoarding was that she lived through the Great Depression. Her family lost all their wealth and had to move out of the large Victorian house she grew up in. That experience also goes a way to explaining her cheapness. She lived to a point of frugality which most would consider acetic. And the cheapness applied to not just what she bought, but what she was willing to receive as well.

“How much was the shirt?” she asked my mother after unwrapping her birthday present one year.

“I’m not telling.”

“Please.”

“$20.”

“Oh,” Gram said, a look of utter anguish on her face, “you have to return it.”

Being cheap by no means limited the amount of stuff she was able to acquire. That stuff just happened to be incredibly cheap thrift shop purchases. I think there was more to her cheapness and hoarding, though, than just her experience of poverty. A similar but separate dichotomy to her sentimality / sophistication, there was a part of her that demanded satisfaction, another drink, another lover, another bite of dessert. And there was the part of her that felt guilty for indulging herself, that she was not worth spending money on. These forces were harder to attribute solely to living through the Depression. Some of the other traumas she went through come into play, her father being killed the week after her birth, her mother dying of cancer when she was only 19. The failed relationships. Recognizing the impossibility of assigning causality, I settle for trying to hold all of these components in my mind as I contemplate the life and death of that thrice-married adventurer who tried so hard to conceal her past, her complexity.

Why did she want to hide? She hid so that she could try to be someone new.

6. Too Much

Why did she hoard? The medical research wasn’t definitive. Cause unknown, but there were different risk factors: living with another hoarder, having experienced a traumatic event, and having a hard time making decisions. It would have been surprising if Gram hadn’t been a hoarder.

In my estimation, she hoarded different items for different purposes. Many were intended as future presents. Throughout my brother’s and my youth, she constantly mailed and handed out presents. They were physical indicators of her love, of your presence in her mind. They were not always the most suitable presents, though.

“What would you like for Christmas? You know Gram will get you whatever you want.”

“Beef jerky,” I told her. Then, two months later, after I’d gotten braces strapped to my faces, I told her no more beef jerky, orthodontist’s orders. By the time she finally realized that I could not in fact eat jerky, years had passed. Though I finally got my braces off, the jerky stopped coming.

She hoarded, too, simply for the thrill of a bargain, the sense that she was getting one up on the world. She checked tags for brands and bragged about name brands she’d gotten for a dollar, though it might come along with a stain or too. Once acquired, these items became a part of her identity, a reflection and validation of her taste; to lose them would be to lose part of herself, to become incomplete, or more incomplete.

The hoarding, too, was an attempt to cling to memory. If our lives and personalities are made up of an accumulation of memories, then anything we get rid of is in a way a letting go of self. Sorting through her belongings certainly made me question my own attachment to things. The inability to let go is in part an inability to grapple with sentimentality, to appreciate while also restricting it.

The mass consumer culture of whiteness is more than ready to fill its cultural vacuum with the idea of stuff-as-self. Sometimes I wonder what it would be like for my parents’ house to burn down, with all my childhood treasures inside lost forever. After anguish, I think I would feel freedom. I would feel closer to Buddhist non-attachment, the antithesis of capital. Non-attachment is antithetical, too, to evolution, which taught us to accumulate in case of emergency. Non-attachment, an anti-biological envisioning of human nature, counterintuitive to the evolutionary need to stockpile, to prepare, to fear.

7. Too paranoid

David, too, has historical justification for his hoarding. As a boy, he was forced to spend six months in the hospital with rheumatoid fever. His parents, forty miles away, only came to visit once a month or so, which must in part account for his hoarding-as-paranoia, his constant expectation that everything and everyone will fail him in a time of need. And whenever one of his tools failed, he felt justified in his hoarding by having another one to use, or at least another one to try to repair.

His hoarding was not only fearful. It was also built on rarely realized ambitions, another piece of furniture to renovate, fencing for a horse enclosure which he’d be able to rent, a cellar full of bottles for wine-making. He was that rare breed of good-natured pessimist, of cynical idealist.

“You’d be dead without Medicare,” I railed. “You wouldn’t have been able to afford your operations.”

“Doctors used to come out and visit you, and if you didn’t have enough to pay, it wasn’t like they wouldn’t take care of you.”

“That was when doctors couldn’t do anything to save you.”

“If everyone has Medicare then it won’t be good anymore.”

“That’s a very selfish position.”

“Sure, I’m old. I want healthcare.”

“What about all the people who can’t afford it?”

“I don’t know.”

“I know. We need universal healthcare. Everyone else has it.”

“In Canada, they have to wait months to visit the doctor.”

“Where’d you hear that?”

“Well, maybe you should look it up on the internet.”

We both shook our heads at each other’s foolishness.

But at least he, too, hated Trump. And we bonded over our disdain for the rich. Though I moved to Schwenksville to better understand Gram, Grampy was the one still around, the one for whom I made dinner every day, who I worked with trying to fix up the house.

8a. Too Many Letters, Cont’d

My impulse to reduce was slowed by Gram’s letters. In sorting through the six boxes stuffed with her letters, I hoped to find some hints of her adventurous youth. Witty jabs from old friends. Inquiries about the status of former lovers. Maybe some of her older letters would have contained these, but most of those had been burned in an apartment fire when she lived in Bryn Mawr. As a result, the letters which I read through were mostly from the past thirty years, a time in which Gram had fairly securely situated herself as “friendly, old woman,” with maybe a little too much lingering fondness for drinking. Not quite the juicy romantic tidbits I was looking for. I had thought that understanding her own romantic blunders would give me strength to move beyond my own. That she kept these stories so closely guarded heightened my desire to uncover them.

I sorted the letters into piles based on who had sent them. There was a pile for friends from the dog club. There was a pile for friends from the Women’s Club. A pile for my mom and a pile for my aunt. There was a pile for former tenants. Of this category, Norman, who had lived as a tenant with Gram in both Bryn Mawr and then the farm, got his own pile. Gram had informally adopted him: an act made clear when he faced the risk of being drafted into the Vietnam War. She called the Peace Corps office every day to make sure that his application was being processed promptly. Other tenants, too, became de facto family members, a potentially precarious financial line navigated gracefully by Gram’s abundance of affection and loyalty. She received letters not just from the tenants themselves but also from tenants’ parents, maintaining written friendships with these people many years after the tenants had gone on their way.

One of the rare splurges Gram allowed herself had been signing up for a sailing trip in Maine. I made a letter pile for the woman she had met at a coffee shop while in port, and that wasn’t the only ongoing correspondence that came out of the trip. There was a pile too for the Cook family, old family friends that Gram’s mother had been supposed to marry into. In an old journal from Gram’s mother that had somehow survived since 1902, I found a letter from Pappy Cook declaring his love for her. His love, though, seemed not very steadfast, as he had married another woman by the time that Ellen Robertson returned from college. Gram maintained this more than 100-year family correspondence without actually telling about the birth of her second daughter, my mother. Presumably, Gram did not want to offend the Cook family’s Southern sensibilities after they’d long since moved from Philadelphia to Alabama. It wasn’t until after Gram’s death that this admission became apparent, when my mom called “Aunt Miriam Ann.”

“Who did you say was calling?”

“Cairn, Bobby’s daughter.”

“Oh, Ann. Oh, I’m so sorry about your mother.”

“No, it’s Cairn.”

“I thought you said Bobby died.”

“She did.”

“Then who’s Cairn?”

“She’s me. Bobby’s daughter.”

“Bobby doesn’t have – didn’t have a Cairn.”

“Yes, she did.”

“Are you sure?”

It took me a month even to divide the letters into piles. And then I had to read through them, a pile at a time, whenever I could work up the gumption to tackle them. I had come to Schwenksville hoping to understand her youth. I realized from the letters that I had to settle for better understanding her old age. But it was not just her old age that I saw a glimpse into, but the old age of her friends, of a generation. The words showed aging itself in her friends’ accounts, the flow of years, of dogs dying, cats dying, husbands dying. Custody battles fought; some won, some lost. Divorces managed. And still, they lived on, wrote on, gardened on, these little old ladies who had to face the onslaught of time. Some of the correspondents were unbearably sentimental. Some of them wrote little, only a line or two that seemed hardly to justify the effort of sending the card in the first place. That, though, from a cyber-age perspective in which the act of ever sending a handwritten letter seems a heroic effort.

They tracked the seasons, these women, noting flowers blooming and snowfalls. Many of them did not mention politics. The few who did mentioned it often. My great-aunt Rachael, a Quaker who paid for my mother’s education, lambasted the Vietnam War, was willing to get arrested in defiance of it. When Gram offered to rent to a black family, she wrote Gram a letter voicing her strong support.

I read of Ann’s decision to move to Mexico with a new husband, tried to pick up hints of the conflicts that lead to their divorce, but there was not much to be gleaned. At least not that I could recognize. I read my mom’s frequent, homesick letters from her time abroad in Scotland, and her subsequent sense of independence and agency at being able to travel around Europe. I read the few thank-you’s that my father had written her, more appreciative than he allowed himself to be in person.

The task of sorting became a burden, but still I continued. I saw Gram not as grandmother any more but friend, unwavering friend, persisting in friendship regardless of lengthy pauses from her correspondents. She was from an era that seems to be dying out, an era of niceness. Though niceness at times could be used to gloss over the troubling injustices of our society, for Gram, not much of a Church- goer, it was a spiritual way of being, rooted in a profound love of people.

“I just want to make people smile,” she told me as we walked along the beach boardwalk. I was in high school and shy with strangers. She said hello to every single person who passed by her.

It is probably a good thing that she did not live to see Trump’s election. That a man so lacking in niceness might be elected president would have pained her to no end. I have at times considered her niceness as trite, as superficial, but as the world descends into seemingly unending cyber-spite, I realize that her desire to instill happiness springs forth from the same call for solidarity that fuels my own socialist stance in the world. Without her example, I would have been colder, more afraid, less willing to commune with the stranger.

8b. Too Much Rain

The photos had been put in a presumably water-tight plastic bin. When I opened the bin, there was a puddle of water inside. The images smelled of mold, even after I’d laid them out to dry in the sun. But the day that I happened to lay them out, a storm came, and they were again drenched. Gram had taken the photos. I wrote to her on them. It was our collaboration.

She is gone. The family picks up the pieces, tries to fill in the center that she occupied. Tries to plan, but there is no planning. We are holding on as long as we can. Not all of us will be sad to see the farmhouse go. Ann has not been there in decades, says all the mess is horrendous.

“What would you want, ideally?” I asked Grampy as he drove me to the train that would bear me away from the Red Rock Rabbit Ranch.

“Maybe in a couple years I’ll move. I’ll have to. But if I leave, there’s no coming back. What if I decide that I want to be here? That I need to be here?”

Martin Krafft received his undergraduate degree in Creative Writing and Economics at Emory University. He is currently a graduate student in photography, video, and imaging at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. He hails from the sweet-tea-drinking part of rural Southern Maryland. His jobs have been many and mostly financially unrewarding: ranch hand, handy man, community organizer, preschool teacher, and video editor for an artist with dementia. His art and writing practice revolves around people’s search for meaning.